Physio Facts - Phantom Limb Pain

Many of our clients have issues with pain in their amputated limb. These fall broadly into two categories: pain in the stump itself and pain in the region that their limb used to be. The latter is known as phantom limb pain and isn’t always pain as such, but often rather peculiar sensations such as “fizzing”, “cramping”, “swelling” or simply being misshapen. For a few patients the pain is extremely severe and distressing and they are not able to get on top of it. This article aims to provide amputees with a variety of ideas that they might wish to try.

PHANTOM LIMB PAIN – What is it?

Firstly, what are phantom limb sensations? Well, there have been many theories debated over the years with the initial blame firmly placed on the severed nerve endings within the stump. These nerves are known as peripheral nerves as they are outside the brain and spinal cord region. However, the consensus of opinion is that there are many mechanisms in the body which are responsible. Imaging studies of the brain show changes in activity when the patient feels phantom pain so it is now thought that both the severed peripheral nerves and the brain and spinal cord are involved in phantom pain.

The severed peripheral nerves have obviously had their normal flow of signals disrupted. These signals usually travel both up to the brain and further down towards the end of the limb. It is very common for a severed nerve to “sprout” extra nerve material into the immediate vicinity. This is known as a neuroma and can become a very sensitive spot if it is just under the skin. Regardless of where the neuroma sits, it has the potential to send abnormal messages up to the brain about what the absent limb is up to – a little like a really bad game of Chinese Whispers! Occasionally, it may be necessary for a neuroma to be surgically removed and the end of the nerve embedded deeply into surrounding muscle tissue.

All peripheral nerves travel up to the brain by way of the spinal cord. As they enter the spinal cord, they make a junction with the next nerve which sends the message up towards the brain. Changes at this junction have been found in patients who have high levels of pain. These changes are akin to an amplifier in this region, enhancing the strength of the signal so that by the time it reaches the brain, the signal is like being at a rock concert. This is known as central sensitisation, or an “upregulation” of the signals. Coupled with this, dampening down signals, which would normally be flowing down the spinal cord, are prevented from being effective in reducing these upcoming messages.

Signals from the spinal cord go on up to the brain, making junctions and terminating in many areas – there is no single “pain” area in the brain. Our brain has the job of making sense of the various incoming signals and deciding what to do about it. Some upcoming signals, like the feel of you having your clothes on first thing in the morning, are quickly recognised as a non-threat and your brain stops registering them. Other signals, like touching a hot iron, are recognised very quickly as needing a speedy response to avoid body damage. When the brain is bombarded with unpleasant sensations, it tries to make sense of them, interpreting them as a burning, cramping or knife-like feeling. The likely response is a desperate need to somehow remove this pain but of course there is nothing there – the limb is absent! The worry and stress that follows from this will contribute to the pain by way of releasing stress hormones. Further on from this, there are some brain changes, known as cortical reorganisation, whereby the area of the brain that represented the amputated area are taken over by the neighbouring region in both the sensory part of the brain and the motor “movement” part. The result of this is that the pain is felt in an ever-increasing area.

Despite phantom limb pain being common in the vast majority of amputees, the good news is that it usually lessens over time both in frequency and duration. For many, it is worse at night and they may have identified certain triggers that seem to set it off. Common triggers include touch, using the toilet, changes in barometric pressure, heat, cold, stress, fatigue and feelings of depression. This is an interesting selection of triggers and reflects both the peripheral nerve and brain changes which are known to occur. Whilst many triggers cannot be changed, it is useful to know that, for example, a change in the weather or a cold spell is going to be a problem.

TREATING PHANTOM LIMB PAIN

There are many surgical, medical and non-medical therapies which have been shown to be somewhat helpful for reducing phantom limb pain. In this article, we will be looking at some of the non-medical treatments that people have tried.

- Graded motor imagery and mirror therapy. This type of therapy aims to re-educate the brain, reversing the effects of the changes described above. Patients are initially encouraged to visualise their absent limb over a period of days or weeks depending on pain response. Once this is mastered without any aggravation of their pain, they move on to using a mirror box which “tricks” their brain into seeing the absent limb. This allows the brain to make sense of abnormal sensations in the limb and dampen them down. Studies are fairly positive in demonstrating a reduction of pain using this method but what is less known is the “dosage” of the treatment. There are also reports of some patient’s pain being made worse by this therapy.

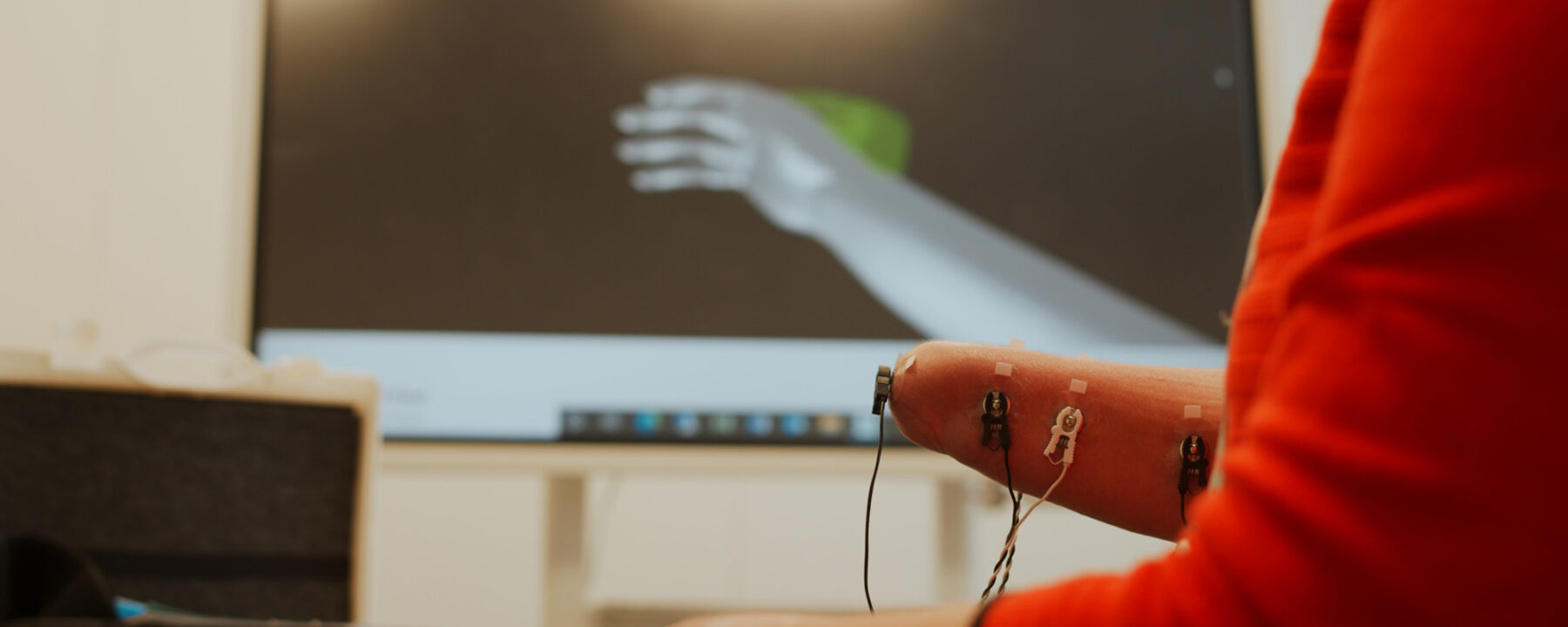

- Neuromotus (virtual reality therapy). This works in a similar way to mirror therapy, but here the absent limb is visualised on a screen and the patient has the ability to control the image by twitching muscles within their stump. These electrical muscle signals are then read by the software and the image displayed. This is a fairly new therapy and initial studies are promising.

- Acupuncture. Acupuncture for phantom pain is normally done on the opposite limb, or may be done on the spine if both limbs are missing. These signals will reach the brain and may affect the way the brain is processing the incoming signals with the result of dampening them down. There have been many studies which demonstrate good pain relief from other conditions using acupuncture but no large trial on phantom limb pain. The most likely explanation for this is the known release of endorphins and other similar “brain chemicals” which act as pain relievers.

- Massage. Some patients find that massaging either their stump or their opposite limb adjacent to their phantom pain can be helpful. Massaging the stump helps to desensitise it, reinforcing messages to the brain where the end of the limb now is. Your physio can advise you on various ways to massage the stump and to desensitise the area.

- TNS. Transcutaneous nerve stimulation has been used to relieve pain in many other conditions but there are no good studies demonstrating effective use for phantom limb pain. This does not mean it won’t work for any individual patient and is probably worth a try as a therapy which will either work or not, without harming the patients. TNS machines use small electrodes placed either where the pain is, on the opposite limb or in a defined position on the back. A tingling sensation is felt under the electrodes which distracts from the pain and encourages the body to produce its own endorphins which can help dull the pain.

- Psychological therapies: mindfulness, cognitive behavioural therapy, distraction, progressive relaxation and meditation have all been used to help reduce phantom limb pain. There is no one therapy that has been proven to work better than others and it might be best to start with simple meditation or mindfulness using an on-line tool to see how you get along. The principle behind psychological therapies is to allow your brain to not concern itself with the incoming information that it is being bombarded with. To either consider something else in the present, such as music, gentle breathing or muscle tension, or to recognise the pain but attempt to link it to non-stressful imagery or behaviour. Seeing an experienced psychotherapist to become more expert in a psychological therapy may be beneficial and there has been positive research in this area regarding reducing phantom pain.

I hope this article has enable you to consider some of the more mainstream non-medical approaches to phantom limb pain. Should you wish to discuss or try any of the above, we would love to hear from you - maryt@dorset-ortho.com